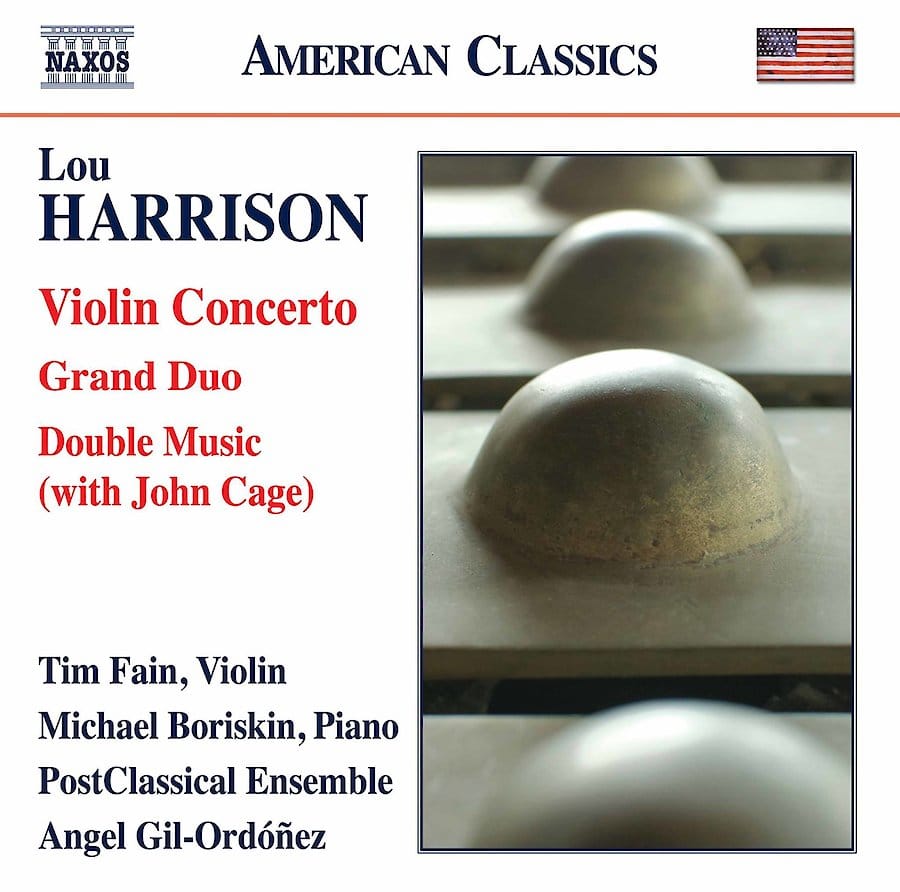

Lou Harrison: Violin Concerto / Grand Duo / Double Music

Summary

Three intriguingly special works, extremely well served by the performers. The recording is altogether first class and one superb homage to Lou Harrison for his 100th birthday.

Remy FranckPizzicato

Brilliant, utterly contemporary writing.

Erica JealThe Guardian

Available on Spotify and Apple Music.

Lou Harrison was a composer far ahead of his time. A protean innovator, he espoused “world music” before it had a name, and this recording documents his pioneering rôles as a composer for percussion and as an integrator of Western and Indonesian idioms. The Concerto for Violin and Percussion, both intimate and vigorous, demonstrates his experimental enthusiasm in the use of non-pitched percussion. The Grand Duo for Violin and Piano is a remarkable example of gamelan-infused chamber music while Double Music, co-composed with Harrison’s friend John Cage, is a well-known product of their celebrated San Francisco percussion concerts.

Reviews

Los excepcionales del mes de octubre de 2017

The result of this recording is simply magnificent. Tim Fain and Michael Borinskin are soloists of great class, and Angel Gil-Ordóñez does an extraordinary job at the helm of his PostClassical Ensemble of Washington.

Harrison: Concierto para violín / Grand Duo / Double Music

The performances are irreproachable, which make this recording the best introduction ever registered to the work of Harrison.

New Release: Hearty Harrison From PostClassical

PostClassical Ensemble celebrates Lou Harrison with a new Naxos recording that is stellar. Harrison was born 100 years ago and it is delightful to have some fresh releases and performances. Tim Fain is the main featured soloist, in Harrison’s Violin Concerto and Grand Duo. Pianist Michael Boriskin (of Copland House) collaborates brilliantly in the gamelan-esque 1988 work with Fain. WBAA’s John Clare spoke with the leader of PostClassical Ensemble, Angel Gil-Ordóñez about the new disc.

Lou Harrison zum 100. Geburtstag

Three intriguingly special works, extremely well served by the performers. The recording is altogether first class and one superb homage to Lou Harrison for his 100th birthday.

Lou Harrison: Violin Concerto review – brilliant, utterly contemporary writing

Lou Harrison had a pioneer’s imagination, not least regarding what might be walloped in the name of music – his Violin Concerto calls for flowerpots, plumber’s pipes and clock coils in the percussion. What’s more striking in this performance by Tim Fain, the PostClassical Ensemble and conductor Angel Gil-Ordóñez is the brilliance of his writing for violin, a collision between itchy dance rhythms and soaring lyricism.

(++++) Concertos and more

Tim Fain plays the work skillfully, and Angel Gil-Ordóñez leads it with his usual flair and sure understanding of music that does not necessarily lend itself to ready comprehension… Gil-Ordóñez brings both knowledge and a sure hand in sound shaping to the performance.

Music for the Lou Harrison Centennial

Harrison wrote the first two movements of Concerto for Violin and Percussion in 1940, and revised them when he created the final movement in 1959. Astoundingly modern, it combines a wild battery of percussion with extremely challenging writing for the violin. Amidst its unbounded inventiveness and jollities, Grand Duo also reflects the gravity with which Harrison viewed the world. A proponent of boundary-less societies, he condemned war and violence, and promoted Esperanto as a universal language.

Review of Lou Harrison: Violin Concerto / Grand Duo / Double Music

To my innocent ears, the performances from hugely regarded musicians are certainly idiomatic, the violinist, Tim Fain, as a persuasive advocate of the Concerto and Grand Duo. Recordings are derived from 2016 sessions. Harrison wrote the first two movements of Concerto for Violin and Percussion in 1940, and revised them when he created the final movement in 1959. Astoundingly modern, it combines a wild battery of percussion with extremely challenging writing for the violin.

The Naxos Interview: Angel Gil-Ordóñez talks with Laurence Vittes

One of Naxos’ April highlights is an all-Lou Harrison CD from the Washington, D.C.-based PostClassical Ensemble; the highlight of the CD is a recording of Harrison’s Concerto for Violin and 5 Percussionists.

About this recording

Presentation

—by Joseph Horowitz, Executive Director of PostClassical Ensemble

Born in Portland, Oregon, in 1917, Lou Harrison was a product of the West Coast: facing Asia. He and his family mainly lived in northern California. As a young adult, he spent a year at UCLA studying with Arnold Schoenberg, then in 1943 moved to Manhattan, the noise and bustle of which disagreed with him. He eventually returned to California: to settle in rural Aptos, near Santa Cruz. Shortly before his death in 2003 he completed a house of his own design near Palm Springs—just as he had previously, with his life-partner Bill Colvig, designed and built an array of home-made musical instruments including an “American gamelan.”

Ongoing explorations of other cultures embroider this sketch. As a child Harrison studied piano, violin, and dance—and also, at San Francisco’s Mission Dolores, Gregorian chant. In San Francisco’s Chinatown, he imbibed Chinese opera (to which he grew far more accustomed than to Mozart or Verdi) and purchased huge gongs to supplement instruments he himself created. The 1939 San Francisco Golden Gate Exposition introduced him to Indonesian gamelan, a life-long passion. He acquired a similar expertise in Korean and Chinese music. His ecumenical bent also led him to Esperanto and to sign language: universal tongues.

His music is an original, precise, and yet elusive product of these and other far-flung cultural excursions. He may also be understood as a composer of paradoxes. His idiom is lyric but never lush. He can be monumental but is not grandiose. His Western forebears are Renaissance, Medieval, and Baroque, not the far more famous Classical and Romantic masters. His American roots are wonderfully protean. American is his self-made, learn-by-doing, try-everything approach. So is his polyglot range of affinities. A composer far ahead of his time, Harrison espoused “world music” before there was a name for it.

The present recording documents twin aspects of Harrison’s art: his pioneering rôle as a composer for percussion, and his pioneering rôle integrating Western and Indonesian idioms. The achievements are linked. Western percussion instruments of metal and wood are largely Eastern in origin. The gamelan bred the xylophone.

Harrison and Percussion

Harrison was powerfully inspired by Henry Cowell (1897–1965)—if not a great composer, an indisputably great catalyst who proclaimed “I want to live in the whole world of music.” Harrison studied with Cowell beginning in 1935. And it was Cowell who introduced him to John Cage (1912–1992)—with whom Harrison plundered junkyards and import stores in search of new percussion resources.

Once Cage moved to San Francisco in 1940, he and Harrison regularly collaborated in percussion concerts. Their instruments included old brake drums and a variety of Japanese, Chinese, and Indian instruments. A well-known product of the Cage/Harrison percussion concerts is Double Music, for which each composer wrote the parts for two of the four players. As Harrison recalled:

“We agreed to use a specified number of rhythmicles [i.e. rhythmic figures] and/or rests of the same quantity, which could be put together in any combination… We wrote separately and then put it together and never changed a note. We didn’t need to. By that time I knew perfectly well what John would be doing, and what his form was likely to be. So I accommodated him. And I think he did the same to me, too, because it came out very well.”

As the eminent American percussionist William Kraft has observed:

“It was totally new to explore Asian percussion and junk percussion, as Cowell, Cage, and Harrison did. They brought percussion to the fore as the primary vehicle of a musical piece. Before that, there were no percussion ensembles. Stravinsky had been a percussion pioneer—in The Soldier’s Tale (1918) he had introduced multiple percussion—you had one percussionist playing several instruments not as background, but as prominent solo instruments, which was astonishing at the time. Cowell, in particular, was a pioneer in bringing in Asian percussion.

“I found Lou’s percussion writing more fascinating than Cowell’s or Cage’s. I think he was the most musical, and the most in tune with sound. I think the Harrison Concerto for Violin and Percussion Orchestra is a masterpiece—you don’t find music like that written by Cowell or Cage. The solo part for the violin is a virtuoso part, extremely well written. And all the sounds, whether produced by maracas or flower pots, are so well integrated that you forget that they’re exotic. He had a way of being expressive, even melodic, using even non-pitched percussion.”

Harrison’s Concerto for Violin and Percussion may be said to combine the experimental enthusiasm of an amateur with the craft of a professional. The first two movements were composed in 1940, then revised in 1959 when the finale was added. Harrison gratefully acknowledged the influence of Alban Berg’s seminal Violin Concerto of 1935: “among the highest musical achievements of the century… It really walloped me.” Berg’s molto espressivo violin writing echoes through Harrison’s fervent score. (He was also instructed by Berg’s example of reconciling tonal and non-tonal procedures.)

The concerto is in the usual three movements. Movement one alternates proclamatory and motoric episodes; for the central section Harrison instructs: “Here the orchestra should finely shimmer & glitter while the violin chants.” There is a solo cadenza in the usual spot. The two main ideas of movement two are a song in stressed long notes and quieter, more intimate music in chains of eighth notes. The finale is a vigorous dance. The score includes copious and precise percussion instructions in Harrison’s exquisite hand—e.g., “For the washtubs, drill holes (4) up from centre on the sides of inverted galvanized iron tubs & suspend by strong elastic cords.” For the coffee cans, “cork or rubber-ended pen-holders make good beaters … & are best for the clock coils as well.”

Harrison and Gamelan

A turning point in the history of Western music occurred in 1889, when Debussy and Ravel first encountered the music of Indonesia at the Paris World’s Fair. A Javanese gamelan performed Eastern music such as they had never heard—not sultry and mysterious, but bright, clean, precise, joyful. Such works as Debussy’s Pagodas (1903) and Ravel’s Empress of the Pagodas, from Mother Goose (1912), imitate gamelan colours, textures, and rhythms. What Hungarian folk music, with its odd rhythms and modes, afforded Bartók, Indonesian music afforded Debussy, Ravel, and countless other composers: a post-Romantic refreshment. Francis Poulenc, Olivier Messiaen, and Benjamin Britten were all prominently influenced by gamelan. In addition, there were ethnographically minded composer/scholars, Western students of Eastern techniques, among whom Lou Harrison achieved a fusion so complete that we can no longer of speak of one culture evoking another.

Harrison first learned to play gamelan in 1975, when a Javanese gamelan visited Berkeley for a summer institute. His teacher was Pak Cokro—one of the foremost twentieth-century gamelan masters. It was Pak Cokro who first suggested that Harrison compose for gamelan. The Harrison scholar Bill Alves comments:

“Lou claimed to have been astonished by the suggestion—but he took it up with enthusiasm, claiming he would be happy never writing for anything else again. In his early gamelan pieces, he applied his experience writing for percussion but also learned and often followed many of the concepts of traditional Javanese composition. Later, he freely drew upon Western and Javanese traditions in unique and enchanting hybrids.

“The idea of a Western composer doing something like this was controversial, especially among Western ethnomusicologists. But I never met an Indonesian who didn’t welcome such innovations. In the West, however, there’s an ongoing debate over whether a Westerner can really appropriate the music of a former colony such as Indonesia in a non-political, non-colonialist way. There is a longstanding suspicion of music that adapts exotic sonorities simply to titillate. Not many people have challenged Lou explicitly—he had a lot of respect as an octogenarian American master. But these sensitivities exist.

“Lou’s attitude was something he inherited from Henry Cowell—that everything in the world should be considered a legitimate influence.”

The present Grand Duo for violin and piano is a remarkable example of gamelan-infused chamber music. Like Harrison’s Piano Concerto of 1985, it embodies Harrison at his most regal. This formidable 35-minute suite originated as a mere Polka composed for the conductor/pianist Dennis Russell Davies; it became the Duo’s celebratory finale. For an opening Prelude, Harrison created hieratic music betokening the magnitude of things to come. Movement two is a Stampede—a rambunctious Harrison genre also to be found in the Piano Concerto. As in the concerto, the pianist uses an “octave bar” for Cowell-like keyboard clusters; the shape of the sculpted foam makes the outer notes speak loudest. Movement three expands a Round composed for Davies’s two daughters seven years earlier. Movement four—the longest—is a long-breathed Air (“Slow and sometimes rhapsodically”) in three parts, the third of which is a varied reprise of the first. The sustained majesty of this music is a function of its steady, gamelan-like course, undeflected by the tension-and-release of traditional Western harmonic practice. The piano’s sharp attacks and tolling octaves evoke gamelan sounds. In fact, the gamelan idiom penetrates in countless ways, obvious and not. The resulting music does not much resemble the music of anyone else. It is certainly music unthinkable from Cowell or Cage.

There is really no one else like Lou Harrison. That he doesn’t fit any musical map is both a proof of his originality and a penalty he pays. One may wonder if there is a more formidable American violin/piano duo than his—and marvel, as well, that it is so seldom performed (except as memorably choreographed by Mark Morris in a version omitting the Air). The absorption of gamelan elements is so complete that the style, global influences notwithstanding, is all of a piece; the finished product cannot be called “eclectic.” Surely today—in our postmodern twenty-first century—we are ready to accept the variety of this composer’s musical landscape, and to celebrate his capacity to embrace it whole.

Program / tracklist

Violin Concerto (1940/1959)

- I. Allegro – Maestoso (7:59)

- II. Largo – Cantabile (7:36)

- III. Allegro – Vigoroso – Poco presto (4:18)

Grand Duo (1988)

- I. Prelude (10:03)

- II. Stampede (6:25)

- III. A Round (Annabel & April’s – 3:57)

- IV. Air (10:40)

- V. Polka (3:45)

Double Music (1941) with John Cage (1912-1992)

Artists

- Tim Fain, violin

- Michael Boriskin, piano

- PostClassical Ensemble

- Angel Gil-Ordóñez, conductor

Discography menu

- Revueltas: Redes / Copland: The City. 2 Classic Political Film Scores

Released in March 2022 - Bernard Herrmann (1911–1975): Whitman – Souvenirs de voyage – Psycho: A Narrative for String Orchestra

Released in October 2020 - Falla: El amor brujo (1915 original version) / El retablo de Maese Pedro

Released in May 2019 - Lou Harrison: Violin Concerto / Grand Duo / Double Music

Released in April 2017 - Silvestre Revueltas: Redes (DVD)

Released in May 2016 - Dvořák and America

Released in June 2014 - Xavier Montsalvatge: Madrigal sobre un tema popular / 5 Invocaciones al Crucificado / Folia daliniana

Released in January 2014 - Aaron Copland: The City (DVD)

Released in January 2009 - Virgil Thomson: The Plow That Broke The Plains • The River (CD and DVD)

Released in January 2007 - Los Sueños de Manuel de Falla

Released in September 2000 - El Abuelo

Released in December 1998 - Música Contemporánea

Released in April 1996 - Film Music by Manuel Balboa

Released in January 1995